- Home

- Entertainment

- Steve Skipper: Colors of Character

Steve Skipper: Colors of Character

God often chooses unlikely paths to display His glory. Steve Skipper, a self-taught African-American artist, didn’t set out to build a career in painting. But when God began stirring his heart, obedience led to canvas after canvas filled with faith. Today, his artwork reflects more than talent. This artist testimony tells the story of a man who paints with God and for His glory.

Painting with God: A Different Kind of “We”

A few minutes into my conversation with Steve Skipper about the documentary on his life, Colors of Character, I realized something. Something powerful, yet simple.

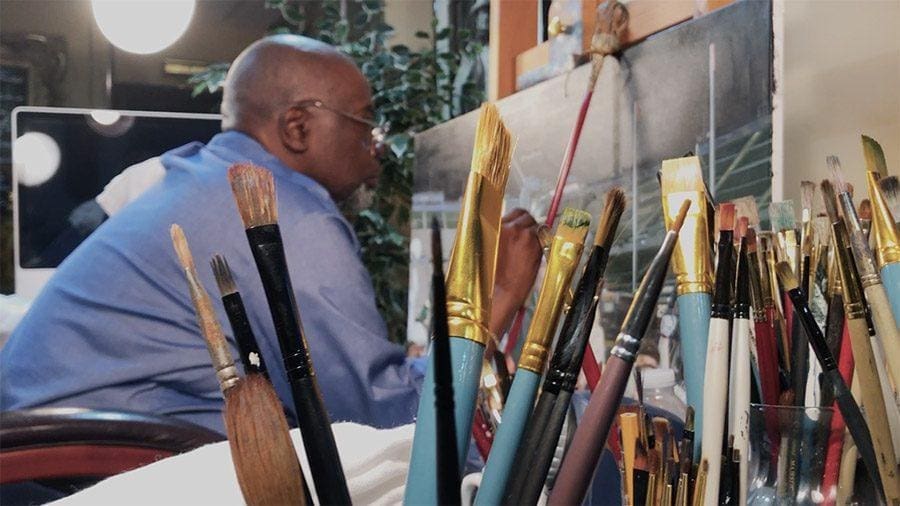

In talking about his art, he always used the pronoun “we” rather than “I.” (For example, he would say, “we did this” versus “I did this.”) I was a little confused at first. There wasn’t another person in the studio with him creating his super-realistic masterpieces. He often works by himself, but he’s never alone.

The “we” he so often referred to was him and God. And he gives all the credit for his artwork to the Creator. This may make more sense when you realize that Skipper has never had any formal training or taken any college-level art classes. His talent is God-taught.

“I can’t paint any better than anybody else, but what’s important to me is the anointing. When it comes from Him, I’m totally different,” Skipper stated. “When I go into the studio, I have to sit down and wait for about 30 minutes and then God comes in and I can feel his hand on mine, and I know it’s time to go to work. But when it’s time for me to stop, he’ll take his hand up and he’ll take it off. I’ll know it’s time to stop.”

Skipper realizes it may sound strange to some, but he equates it to Jesus’ words in John 10:38: “but if I do, though you do not believe Me, believe the works, that you may know and believe that the Father is in Me, and I in Him.” Skipper isn’t claiming to be Jesus or anything like that, but instead he’s simply asking others to believe the miracle that our Lord Father performs through his hands and paintbrushes.

His faith and relationship with Christ wasn’t always this way.

Growing Up in Alabama: Talent, Turmoil & Identity

Skipper was born in Homewood, Alabama, on January 13, 1958, and grew up in Rosedale, not far from Birmingham.

In the fourth grade, his teacher Ms. Vernelle Saunders noticed his artistic talent. She encouraged young Skipper to embrace his passion, even purchasing art supplies for him out of her own salary. He was intimidated at first by all the different types of paintbrushes, the blank canvases, and the oil paints that came in tubes and smelled nice.

His uncle and older brother created art, and like most younger brothers, Skipper wanted to be just like his brother, Don. His uncle struggled as an African-American artist in Alabama and eventually moved to California.

“They were doing a little bit, not really sophisticated art, but sketching and stuff like that. They were very good at it. I loved my brother and I wanted to be like him.”

Although his uncle was an artist and Ms. Saunders spoke to his parents several times about Skipper’s artistic abilities and how to nurture it, his mom was adamantly against him pursuing art. Her mindset was that “no black man can make a living as an artist.”

When he was nine, Skipper walked in on his mom having an affair. Although his parents stayed together, the damage was already done. The marriage deteriorated, and Skipper had a difficult time coping with what he had witnessed.

Unfortunately, things at school weren’t any better. In 1968, when Skipper was 10, the city integrated the schools by bussing children from African-American neighborhoods to the more affluent white schools. There were many fights between the white and black students.

Because of his home life and his school situation, he was extremely angry. And for the most part, he internalized it. This anger seethed within him from the time he was nine until he was 13. That’s when his cousin introduced him to marijuana. It was the answer he was looking for. When he smoked, all his pent-up anger evaporated.

A few months later, he was introduced to the notorious street gang, the Crips. After getting beaten up by members, he was initiated. Within the gang, he found brothers and family, something that was missing at home. His role in the gang was to sell drugs at school – to students, teachers, and other faculty members. He would arrive every morning at school with a backpack full of drugs and would leave every afternoon with it filled with money. The money, new clothes, and everything else that came with being part of the gang was too alluring to give up.

From Anger to Salvation: A Radical Turning Point

Then during his junior year of high school, his life changed. He was at a park smoking weed with other gang members when “Big Mike,” who was not in the gang, asked to speak to Skipper alone. Big Mike told him about God and that He had a purpose for his life.

A little while later, Big Mike invited Skipper to a revival at a nearby church. He agreed to attend under one condition – that Big Mike never talk to him about Jesus again.

“I told him if I go into the church and they start singing and stuff like that and they get excited and everything, I’ll just slide out the door. So I made plans to meet this guy outside the church and I was going to start taking speed that night. My plan was to go in for 15 minutes, but God’s plan was totally different from mine and I ended up staying there.”

Skipper never met up with the guy to try speed. In an ironic twist of fate, the speed they were going to take that night had been laced with some dangerous chemicals and would’ve probably killed him.

Then on December 23, 1976 – his junior year of high school – Skipper was saved.

“When I first got saved, it was radical. It had to be because of the demonic activity that was in my life. I’d been to church before, but all the demons that were in my life, they wouldn’t be laughing now. The minister that ministered to me was extraordinary. He was a different kind of minister that really brought the word of ministry to me that I’d never seen before.”

Having been saved and given up the gang lifestyle, Skipper faced a conundrum. He had to leave the Crips, but the only way out was to die. He didn’t want to die, but knew he could no longer be a member of the gang, so he gathered up the courage to walk in and tell them that he was quitting.

“My change was so radical, believe it or not, I walked right out of the gang thinking they were going to kill me, but they didn’t because the shock I think was too tremendous.”

When Obedience Meets Opportunity

During high school, Skipper was a good enough football player to receive two scholarships to play football in college. He also received a scholarship to study fine arts at Florida State University. God, however, had different plans.

“God told me not to take the scholarships because He wanted to teach me everything I know about art. He wanted the glory for it.”

Skipper did what God told him to do and turned down the scholarships, which, as one may expect, didn’t sit well with his parents.

After high school, Skipper was working at a steel company when a pipe crushed his right hand (his painting hand). He vividly remembers hearing the devil say, “you’ll never paint again.”

He was devastated, but he didn’t let that setback deter him. Although Skipper was skeptical to return to painting with his hand still healing from the accident, he did so because God told him to. It was during that time when he first felt God guiding his hands and every stroke of the paintbrush. Eventually, his hand completely healed and he could paint again without assistance, but God’s guiding hand never left.

His first endeavor into professional art was biblical paintings and Christian artwork. When God told Skipper to create a business, he started painting portraits for a local high school baseball team that he would sell for $35. The name of his company? Anointed Homes Art.

Becoming the First African-American Artist for Alabama Football

Then one day he met a guy at a frame shop who worked for Birmingham’s now defunct semi-pro football team. One opportunity led to another, which led to another and then another. Skipper’s sports art business was soon booming.

His impressive list of sports clientele includes the Atlanta Falcons, Atlanta Hawks, Auburn University football team, UAB Blazers football team, former Green Bay Packers Quarterback Bart Starr, former Dallas Cowboys Tight End Jason Witten, former Washington Redskins Quarterback Doug Williams, legendary Grambling State football coach Eddie Robinson, the PGA, NASCAR, and more. He’s currently working on a piece for legendary Florida State football coach Bobby Bowden.

Perhaps Skipper’s most prolific subject matter in the world of sports is the University of Alabama football team. A quick glance at the gallery on his website shows more than a dozen different paintings highlighting different players who suited up for the Crimson Tide.

Prior to working with the university, Skipper met former Alabama Head Coach Mike Shula at an inter-squad practice between the Atlanta Falcons and the Miami Dolphins. Shula asked Skipper why he didn’t do anything with the University of Alabama. Skipper’s response was short and honest, “I don’t know anybody at Alabama.” Shula promised to introduce him to Alabama’s Head Coach Perkins. From there, his relationship with the school ignited.

Skipper became the first African-American artist to do artwork for the University of Alabama.

When God Redirects Success Toward Purpose

There is a lot of money to be made in sports art. However, there is not much market for civil rights art.

That, however, didn’t matter to God.

After Alabama won the National Championship in college football, Skipper’s business was flourishing. He was taking tons of orders for Alabama-themed art. People called the studio right and left, asking if he was going to paint something to commemorate the school’s most recent title. But then God threw a wrench into his plans.

“All of a sudden God speaks to me and says, ‘We’re not going that way.’ I said, ‘Sir?’ I’m sitting there thinking that all of this is happening because you’re blessing me. Then he said again, ‘We’re not going that way this time, we’re going this way. We’re going to do civil rights artwork.’”

Skipper thought the devil was talking to him, but to him it’s the first time the devil sounded exactly like God because this didn’t make any sense. He quickly realized that it was indeed God.

“I know His voice. I’ve known His voice ever since I was saved, and I know this is Him. I said, ‘God …’ I’m actually asking the Creator of the universe, ‘Are You sure?’ He replied, ‘We’re going this way.’”

So, Skipper started creating civil rights art.

Painting the Civil Rights Movement

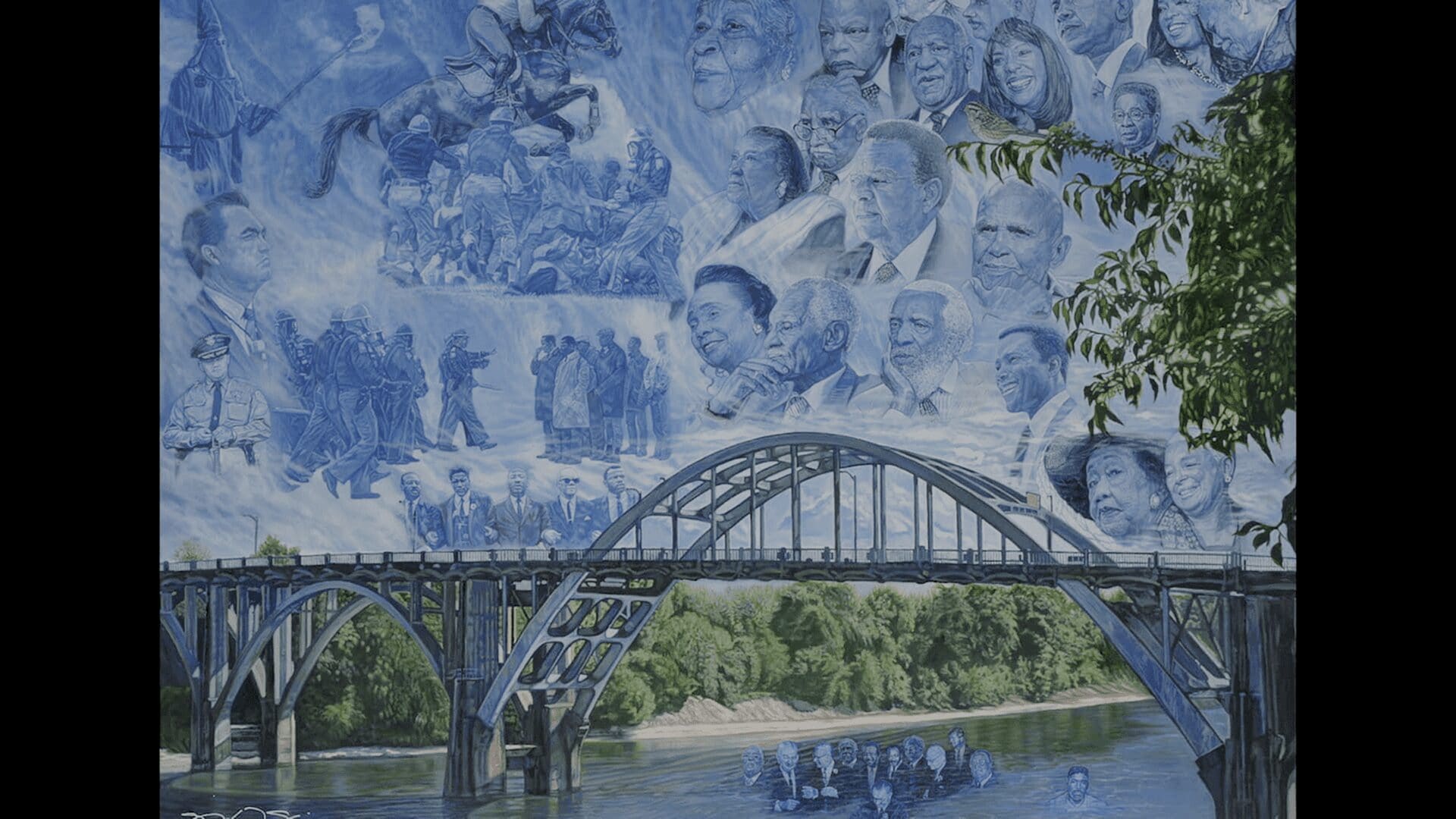

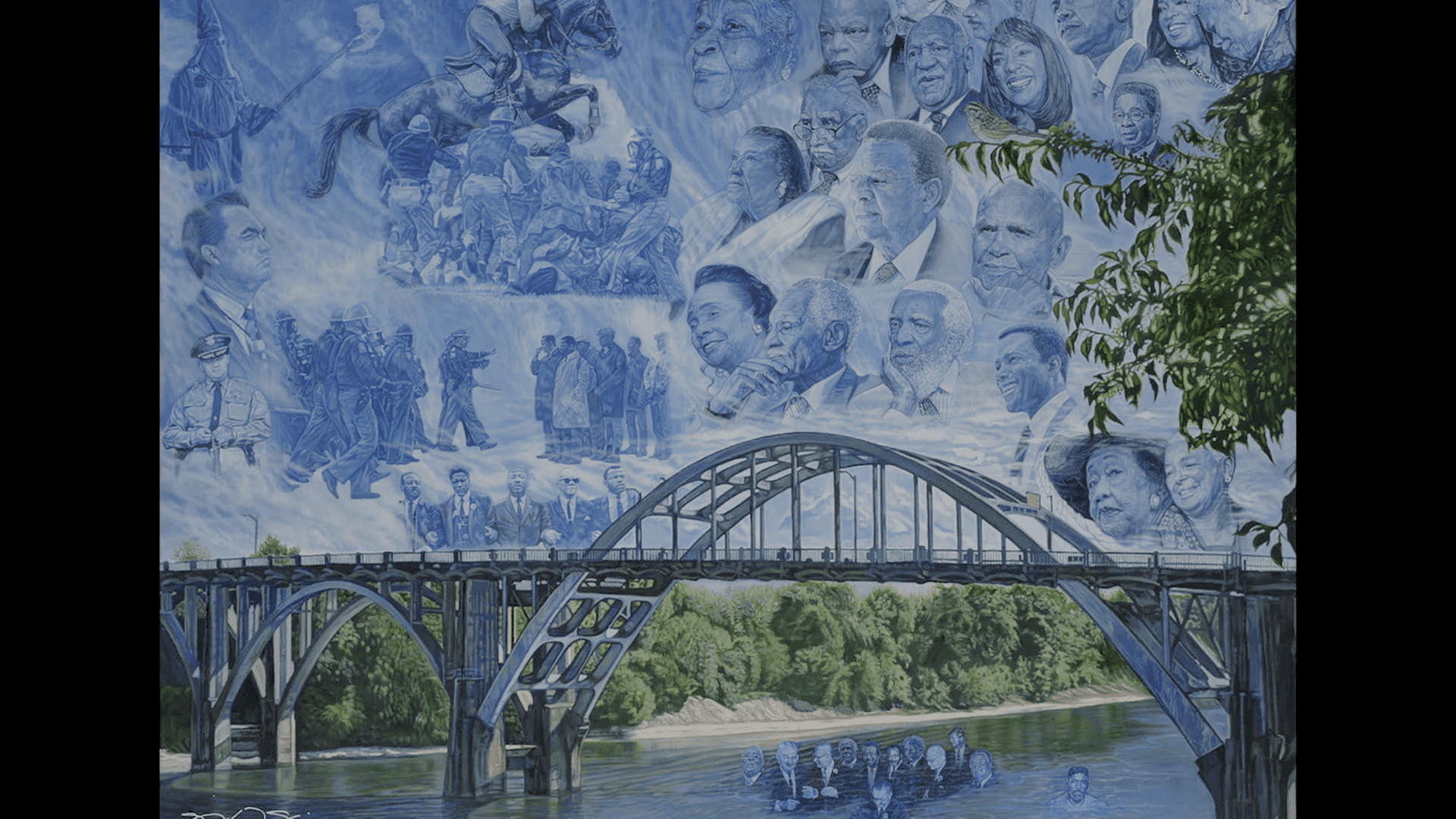

The Mayor of Selma, Alabama – the site of Bloody Sunday on March 7, 1965 – asked Skipper if he would do a commemorative painting for the 50th Anniversary of the historic event.

“The best thing that happened to me was getting to meet C.T. Vivian, Ambassador Andrew Young, and Congressman John Lewis. We do a painting celebrating the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday at Selma, and I get to meet all these guys. They not only bring me in to meet with them, but they endorse this thing, which has never been done before. They’ve never endorsed anything together like that.”

The Selma to Montgomery marches were a series of three marches advocating for voting rights. John Lewis and Hosea Williams led a group of about 600 demonstrators from the small town to the state’s capital.

The group didn’t make it far. On the outskirts of town, as the group crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge that spanned the Alabama River, a large group of state troopers met them. According to the article, “How Selma’s ‘Bloody Sunday’ Became a Turning Point in the Civil Rights Movement,” on History.com, the troopers “knocked the marchers to the ground. They struck them with sticks. Clouds of tear gas mixed with the screams of terrified marchers and the cheers of reveling bystanders. Deputies on horseback charged ahead and chased the gasping men, women and children back over the bridge as they swing clubs, whips and runner tubing wrapped in barbed wire. Although forced back, the protestors did not fight back.”

Art That Honors History and Unites Voices

The bridge features prominently in Skipper’s piece commemorating the horrific day. Above the bridge, are images of different faces of the civil rights movement. He included all races, genders, and walks of life, indicating that the fight for civil rights and equality has always been won by alliances where voices are raised and not silenced.

The daughter of former President of the United States Lyndon B. Johnson requested a private showing of the piece. She asked that the first print be placed in her father’s presidential library, which Skipper was happy to oblige. President Johnson signed into law the Voting Rights Act on August 6, 1965, prohibiting racial discrimination in voting.

Shortly after he finished the Bloody Sunday art, Bob Baumhower of the Miami Dolphins called Skipper. He asked him if he knew that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. went to Bimini in the Bahamas to write his Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech.

Skipper was unaware of this, so Baumhower asked if he’d like to go visit. “There’s a place in the mangroves in the Bahamas where he sat down and wrote his speech.” Next thing he knows, he’s talking to government officials in the Bahamas about visiting Bimini.

A Legacy Painted for God’s Glory

Since Skipper had never been out of the country, he had to get a passport to get to the Bahamas. But once he arrived in the island nation, they commissioned him to do a painting of the scene where Dr. King wrote.

Ambassador Young heard about it and wanted to see Skipper’s painting of the mangroves with a bust of Dr. King sitting among them. The ambassador told a friend of his who owns a museum in Atlanta. The museum owner is a friend of England’s Prince Charles, who saw it and loved it. Skipper was getting ready to present a print of it to Prince Charles before Covid hit.

The Bohemian Prime Minister also requested a print for placement in the Nassau airport.

In Skipper’s own words, the overall message of Colors of Character “is to find out exactly what God wants you to do, what He created you to do, because that’s the only thing that’s going to make you happy and affect the world.”

And that’s exactly what Skipper’s art is doing.

…

Celebrate faith-filled stories of courage and calling.

👉 Explore more inspiring Black History Month features on our YouTube Black History Playlist.

Trending Now

Sign up today for your Inspiration Today Daily Newsletter

Supercharge your faith and ignite your spirit. Find hope in God’s word. Receive your Inspiration Today newsletter now!

John Farrell

John Farrell serves as the Digital Content Manager at Inspiration Ministries, where he oversees the planning, organization, and management of website content to support the ministry's global digital outreach. With a strong background in writing and editorial strategy, John ensures that the articles, devotionals, and discipleship resources on Inspiration.org are accurate, engaging, and aligned with the ministry's mission.

John has authored more than 1,000 articles, press releases, and features for Inspiration Ministries, NASCAR, Lionel, and Speed Digital. His versatility as a writer is also showcased in his 2012 book, The Official NASCAR Trivia Book: With 1,001 Facts and Questions to Test Your Racing Knowledge.

A graduate of Appalachian State University, John brings excellence and attention to detail to the digital experience at Inspiration Ministries. He lives in Concord, N.C., with his wife and two sons.

Related Articles

March 10, 2025

Finding Total Victory on the Road to Championship

I have been playing competitive golf for 55 years. Through the various stages of my life, my…

March 7, 2025

Average Joe Movie: SCOTUS, Praying Football Coach Backstory

When Coach Joe Kennedy knelt to pray at the 50-yard line after a high school football game, he had…

February 28, 2025

The Power of Story: A Muslim Journey to Hope

Storytelling is one of the oldest and most powerful ways to touch the human heart. Parents tell…

February 27, 2025

‘Harriet’ Movie: Courage, Freedom, Faith

Antebellum abolitionist Harriet Tubman had convictions and courage that helped free herself…

Next Steps To Strengthen Your Walk

Inspiration Today Newsletter

Supercharge your faith and ignite your spirit. Find hope in God’s word. Receive your Inspiration Today newsletter now!

Christian Articles

Find articles to strengthen your walk and grow your faith. We have a wide range of topics and authors for you.

Submit A Prayer Request

We are here for you. Simply click on the button below to reach us by form, email or phone. Together we will lift our hearts and voices with you in prayer.