- Home

- Relationships

- How Can They Think That?

How Can They Think That?

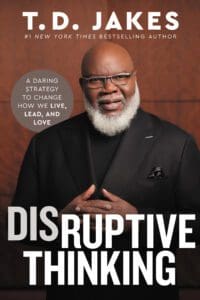

Excerpt taken from Disruptive Thinking by T.D. Jakes.

Excerpt taken from Disruptive Thinking by T.D. Jakes.

Chapter 6

Why It’s So Difficult

Everyone Has Invisible Fences and Internal Torments

When I was the pastor of a small storefront church in West Virginia, a white lady came to my church one Sunday and said she had watched me on TV. She had traveled to Charleston to find my church.

“Can white people come to this church?” she asked me.

I was astounded. I thought, Y’all can go anywhere you want to go. But that was my Black perception talking. It was naive on my part to think white people don’t have invisible walls. It’s similarly naive for any of us to think that rich people don’t have invisible walls. We usually have no way of knowing what the next person is dealing with, what shame or guilt might be tormenting them.

In Genesis, when Joseph is visited in Egypt by his brothers who are hoping to buy grain from him, we come face-to-face with the pain of the tormentor. Because of his brilliant interpretation of Pharaoh’s dream, that there would be seven years of feast and seven years of famine, Pharaoh has installed him in the position of governor of Egypt. He had been sold by his brothers into slavery, but now he has risen to this elevated position of prince, riding the chariot right behind the king. He has moved on from his early hatred of his jealous brothers for what they did to him and has decided to forgive them. When they come seeking grain, Joseph recognizes his brothers right away, but they don’t recognize him. He hears them talking in their Hebrew tongue and doesn’t let on that he understands them. But what they are saying reveals their guilt and torment about what they did to Joseph many years before. They have suffered, just as Joseph has. What a powerful life lesson that offers to us all: no one escapes.

The dude walking around the hood with his pants sagging, wearing an angry scowl, is really not that different from the guy sitting in the C-suite. They are both tormented by invisible fences — and their torment often dictates their decision-making. One might join a gang and commit petty crimes; the other might drink himself to sleep at night or bury his pain in illicit affairs. As I travel the world, preaching in pulpits across the globe, to just as many white people as Black people, the thing that has startled me most is the realization that everybody’s got a story. We all have our stuff.

When we become comfortable with disruption and have settled on the other side of the fence, at some point we come upon a discovery: we’re not done yet. We keep encountering new fences we must jump. That’s because life keeps changing. When I read Nelson Mandela’s 1995 autobiography Long Walk to Freedom, I was inspired when I came across a powerful passage on the final page of the book: “So I spent my life to climb to the top of the hill, a bit winded and tired. I sat down exasperated and a bit in shock, because I spent my life to climb this mountain to get to the top, only to find out that there are more mountains to climb. So I think I’ll sit here and rest a while.”

That’s life. When we jump the fence and get to a point of mastery, we discover there are more fences to jump. For some of us, that’s an alarming discovery — so terrifying we don’t want to jump anymore; we’re content to stay where we are. Others will keep jumping. David was so shrewd of a fighter that he killed the lion who held the lamb in his mouth without hurting the lamb. And his reward for getting the lamb out of the jaws of the lion? A looming bear. So David killed the bear. And his reward for killing the bear was the right to fight the lion.

The prize for winning the fight is the right to enter into the next fight. All of David’s life was a succession of battles that were trophies leading to him being king. And so it is with our lives: we have to learn to flourish in disruption, amid the fight.

I had a revelation when I realized the real prize of life is not the comfort that may come with riches; the real prize is the fight it takes to get there. When we decide to value the fight, we’ve already won the battle. We have to learn to savor that leap across the fence. That’s what the gladiator feels when he goes out to fight-that spark of dopamine coursing through his body as he gears up for another battle. That’s why prize fighters who have retired often climb back into the ring, because they’re never happier than when they are fighting. For me, the fight is like a drug, one of the best feelings I’ve known. It’s the gas that makes my engine roar.

The epitome of disruptive thinking is relishing the race, not the trophy at the end. Enjoying the sensation of your lungs feeling like they’re about to explode, the joy of the ribbon brushing your chest as you hit the finish line. The medal they hand you is sweet, but it’s really just something to stash away in a drawer or to collect dust on a shelf.

When I realized I am a gladiator, I couldn’t help but to think back on my childhood years, when I could feel the sting of my father’s disappointment that I wasn’t going to be an athlete. I now know that I might not be able to throw a spiral, but I’m everything my father was-just on a different playing field. That was a profound revelation for me.

…

Click here to learn about Bishop T.D. Jakes’ show, “The Potter’s Touch,” and when to watch it on Inspiration TV.

Order your copy of Disruptive Thinking by T.D. Jakes.

Trending Now

Sign up today for your Inspiration Today Daily Newsletter

Supercharge your faith and ignite your spirit. Find hope in God’s word. Receive your Inspiration Today newsletter now!

T. D. Jakes

T. D. Jakes is a New York Times best-selling author of more than forty books. He is the CEO of the TDJ Enterprises, spanning film, television, radio, publishing, podcasts, and an award-winning music label. He is also a Grammy Award-winning music producer. Learn more at tdjakes.org

Related Articles

April 25, 2024

When We Hurt Those Who Are Hurting

People in the church often say foolish and hurtful words to those who are grieving. “If I were you…

April 24, 2024

Loving Prickly People

Have you ever had that one person in your life? You know, that one person who seems to be able to…

April 17, 2024

Who’s in Your Corner?

For a monumental fight, if you want to go the distance, you need something worth fighting for and a…

Next Steps To Strengthen Your Walk

Submit A Prayer Request

We are here for you. Simply click on the button below to reach us by form, email or phone. Together we will lift our hearts and voices with you in prayer.

Partner WIth Us

Sow a seed of faith today! Your generous gift will help us impact others for Christ through our global salvation outreach and other faith based initiatives.

Inspiration TV

Watch Christian content from your favorite pastors, christian movies, TV shows and more.