Related Articles

Finding Total Victory on the Road to Championship

I have been playing competitive golf for 55 years. Through the various stages of my life, my…

Average Joe Movie: SCOTUS, Praying Football Coach Backstory

When Coach Joe Kennedy knelt to pray at the 50-yard line after a high school football game, he had…

The Power of Story: A Muslim Journey to Hope

Storytelling is one of the oldest and most powerful ways to touch the human heart. Parents tell…

‘Harriet’ Movie: Courage, Freedom, Faith

Antebellum abolitionist Harriet Tubman had convictions and courage that helped free herself…

Next Steps To Strengthen Your Walk

Inspiration Today Newsletter

Supercharge your faith and ignite your spirit. Find hope in God’s word. Receive your Inspiration Today newsletter now!

Christian Articles

Find articles to strengthen your walk and grow your faith. We have a wide range of topics and authors for you.

Submit A Prayer Request

We are here for you. Simply click on the button below to reach us by form, email or phone. Together we will lift our hearts and voices with you in prayer.

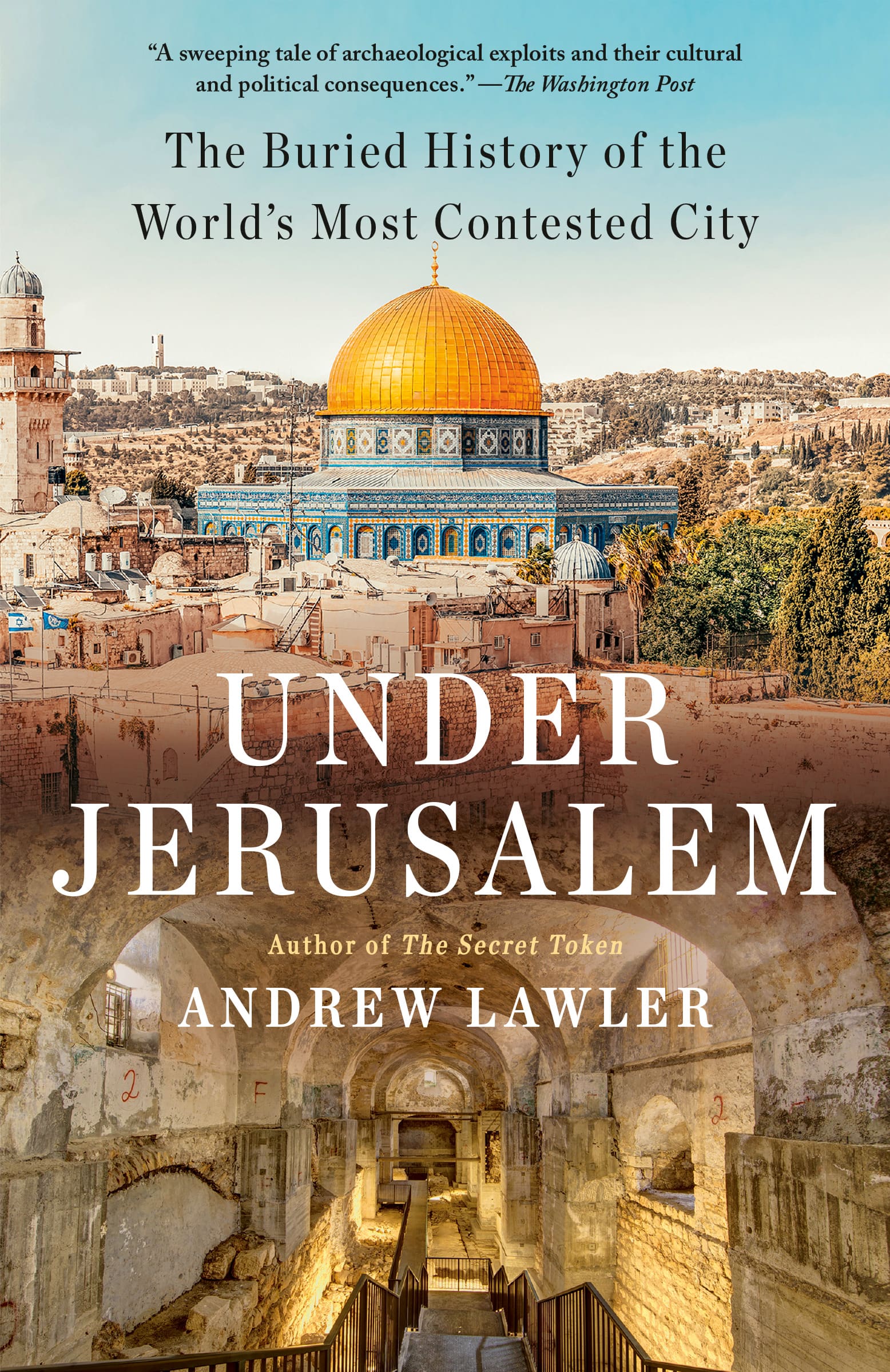

Excerpt taken from Under Jerusalem: The Buried History of the World’s Most Contested City by Andrew Lawler

Excerpt taken from Under Jerusalem: The Buried History of the World’s Most Contested City by Andrew Lawler