- Home

- Entertainment

- Johnny Cash: End of the Line

Johnny Cash: End of the Line

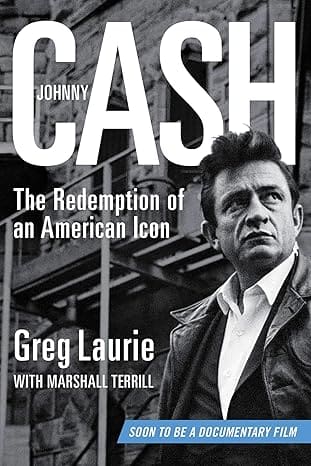

Excerpt taken from Johnny Cash: The Redemption of an American Icon by Greg Laurie with Marshall Terrill

Excerpt taken from Johnny Cash: The Redemption of an American Icon by Greg Laurie with Marshall Terrill

Chapter 15

End of the Line

Everyone was plotting against me. If I saw a police car, I’d duck down a side street, then drive like mad through residential areas, narrowly missing innocent pedestrians. Why I didn’t kill anyone, I don’t know— or maybe I do know. — Johnny Cash

His hit records, money, and fame didn’t get Johnny Cash special accommodations at the El Paso city jail. The worst dump he’d ever stayed in on the road was better than the cramped cell he now occupied. The toilet didn’t flush; his bunk was a ratty blanket tossed over hard bed springs. The overhead light remained on 24/7, making it impossible to ignore the mad scurrying of cockroaches everywhere.

Cash heard occasional laughter and loud cursing coming from neighboring cells. Somewhere, an inmate cried hysterically, and another frantically beseeched God for mercy. Cash tried to pray himself, but he was too wired and distracted by the constant din. Finally, he crashed, and as he slept, word of his arrest traveled to newspapers and radio and TV stations around the world.

His breakfast the next day was a bowl of black-eyed peas and a piece of bread. Three times Cash was brought out of his cell to take phone calls from concerned friends and associates. After the third one, he told the guard he was no longer available to callers and sank down on his bunk, utterly despondent. He had ruined his life and let down family and friends. He imagined his daughters hearing about what happened and crying, and he started to weep himself.

“I don’t ever want out of this cell again,” he sobbed. “I just want to stay here alone and pray that God will forgive me—and then let me die.”

The most miserable man or woman around is the one who knows the will of God and does not do it. Johnny was that man.

He sang so often of people living lives of crime that many thought he was a serious criminal himself. But now Johnny was seeing what a life behind bars, albeit a short one, was really like. He fell into a state of deep despondency.

King David, after his fall into sin, was guilty of crimes far worse than Cash. David not only committed adultery, but he also played a role in the murder of an innocent man—the husband of the woman he had the affair with.

Describing how he felt at this time, David wrote:

When I kept it all inside,

my bones turned to powder,

my words became daylong groans.

The pressure never let up;

all the juices of my life dried up.

Psalm 32:3-4 (MSG)

Johnny Cash could have written those very words at this stage of his life.

His old belligerence returned as Cash, wearing a black suit and white shirt, was marched to a bond hearing arranged by local lawyer Woodrow Bean, who’d been hired by Marshall Grant. Seeing a phalanx of photographers and reporters recording the scene, Cash angrily swore at one and threatened to kick another. But he was appropriately somber in the courtroom as U.S. Commissioner Colbert Coldwell read the indictment charging him with “willfully smuggling and concealing drugs after importation.”

Coldwell set Cash’s arraignment for December 28, released him on a $1,500 bond, and ordered him not to leave the United States.

He went home to Casitas Springs with his tail firmly tucked between his legs. Vivian and the kids welcomed him with open, loving arms, and Cash came clean about his addiction. He vowed to kick it. For the first time in his life, he said, he felt real shame.

Shame has its place in a person’s life. It means your conscience is working.

“Are they ashamed of their disgusting actions? Not at all—they don’t even know how to blush!” (Jeremiah 6:15 NLT)

But Johnny had not gone that far—yet.

Six weeks later, he returned to El Paso to face the music. Vivian accompanied him. Cash pleaded guilty to possession of illegal drugs, a misdemeanor that carried a maximum fine of $1,000, one year in prison, or both. The district judge deferred sentencing indefinitely, pending a report from Cash’s probation officer, and Cash was free to resume his touring without restriction.

Plenty of concert dates had been cancelled in the immediate wake of his arrest, but it didn’t take long for Cash to pick up right where he’d left off.

Unfortunately, this also applied to his abuse of amphetamines.

The following March, Cash set out for a string of concert dates in Canada and New York State, including a three-night stand at Toronto’s prestigious O’Keefe Centre for the Performing Arts. No country artist had ever played there before, and manager Saul Holiff left no stone unturned to promote the engagement. He even got Cash to sit down with reporters and take questions about El Paso. He was contrite, humble, and made a good impression.

“It was my first conviction of any kind,” Cash said. “Of course, I can’t goof up like that again.”

But for all of Cash’s public talk of having put drugs behind him, Holiff knew it wasn’t so. His behavior at the Four Seasons Hotel— running around naked in the hallway, pounding on doors in the middle of the night—told a different story.

All three O’Keefe Centre shows were sold out, and Holiff held his breath each time Johnny took the stage. One time, he came out and faced the wrong way, and at the final show, Tex Ritter, the cowboy singer who was a supporting act on the bill, had to push Cash out on stage. Johnny wasn’t even wearing shoes, just socks. But somehow that and his addled condition didn’t keep him from giving a performance that wowed fans and critics.

Saul Holiff sank into his bed later that night relieved and exhausted. Then the phone rang.

“There’s something wrong with Johnny,” said June Carter breathlessly when he answered.

They were supposed to be in Rochester, New York, the next day for afternoon and evening shows. Abe Hamza, the Rochester promoter, was a large, menacing, cigar-smoking Godfather type who’d warned Holiff he would personally break both his legs if he failed to deliver Cash.

Saul flew out of bed, out of the hotel, and to Cash’s motor home in the parking lot. A crowd of performers and others milled around the entrance of the vehicle when he arrived, each face he saw looking grim. When Holiff pressed his way inside the motor home, there lay his star on the floor, unconscious. Saul knelt, grabbed Cash’s wrist and checked for a pulse. Nothing. Someone else put an ear to Cash’s chest and reported the same result.

Holiff joined the others back outside, and as Cash lay apparently dead or dying, a raucous debate ensued about what to do. Wellesley Hospital was nearby, said someone, but somebody else pointed out that Toronto General had a better reputation. American hospitals were best, said another—but if they made a pell-mell dash for one and got searched at the border, Lord only knew what contraband would be found in the motor home, and they’d all take a fall for it.

Unable to shake the image of a glowering Abe Hamza out of his head, Holiff decided to head straight for Rochester, three-plus hours away, and hope for the best. June and Marshall Grant rolled Cash in a blanket and off they went. The border crossing was blessedly uneventful, and they made it to the Rochester Memorial Auditorium at 2:30 the following afternoon. Holiff went back to check on Cash and almost went into cardiac arrest himself when he found Johnny sitting up and drinking coffee as if he’d just awoken from a good night’s sleep.

“How are you doing?” asked the almost hyperventilating manager.

“Why are you asking me how I’m doing?” responded Cash in genuine puzzlement. “What do you think I’m doing? I’m going to go out and give a show.”

He did two sensational shows that day. Even Abe Hamza smiled.

Johnny was really skating on thin ice. God would graciously give him another chance, but he would return to his old ways again.

The concerted PR effort to present Cash to the public as a regular, fun-loving guy whose worst days were behind him included the recording of Everybody Loves a Nut, a thirty-minute album of goofy novelty tunes complete with a cartoon cover. A single on it called “The One on the Right is on the Left” reached No. 2 on the country singles chart, but the album tanked overall. Today, it’s actually considered something of a classic and beloved by a whole new legion of fans. Cash had a skewed view of it years later.

“I think that came out of amphetamines,” Cash said. “It was part of my craziness at that time, and it happened to find its way onto the tape. I thought some of the songs were funny. And I thought it might show that I did have a sense of humor. But there were no great songs on that album, that’s for sure.”

In May 1966, the craziness continued. That’s when Cash went on a tour of the United Kingdom and Europe. Bob Dylan was touring overseas at the same time. They met and partied at Dylan’s hotel in Cardiff, Wales. Cash was booked at the prestigious Olympia Theatre in Paris, but when Saul Holiff went to meet him at Heathrow Airport in London for the flight to Paris, Cash was a no-show. Holiff was so furious he immediately tendered his resignation as Cash’s manager and spent a week walking around Hyde Park to recover his equilibrium. Six weeks later, he and Cash reconciled.

Back in California, Vivian Cash was in bad shape herself. The overwhelming emotional stress and strain of the past few months had worn her down to a mere ninety-five pounds, and when she went to see a doctor, he was blunt.

“You need to do something,” he said. “If you don’t, somebody else will be raising your girls.”

That cut it for Vivian. In June, when Cash returned from Europe, instead of coming home, he camped at the Nashville home of Columbia Records executive Gene Ferguson. It was no coincidence Ferguson’s abode was close to June Carter’s house.

Vivian got herself a lawyer, and on June 30, she filed for divorce, charging Cash with extreme mental cruelty. She was wracked by guilt and misgivings and even called Cash in Nashville to ask if there was any chance of them reconciling. He was high and incoherent, and Vivian heard June in the background telling Johnny to hang up the phone.

“No,” he managed to say. “It’s too late.”

Vivian was awarded the Casitas Springs house and some other property, alimony of $1,000 a month, child support of $1,600 a month, and 50 percent of royalties on all songs Cash wrote and recorded up to 1966.

What she didn’t get was closure. That would come much later.

Decades later.

…

Order your copy of Johnny Cash: The Redemption of an American Icon by Greg Laurie with Marshall Terrill

Trending Now

Sign up today for your Inspiration Today Daily Newsletter

Supercharge your faith and ignite your spirit. Find hope in God’s word. Receive your Inspiration Today newsletter now!

Greg Laurie

Greg Laurie is the senior pastor of Harvest Christian Fellowship in Riverside, California, and the founder of Harvest Crusades, a nationwide evangelistic event that has drawn in more than 8.8 million people since 1990. Learn more at harvest.org

Related Articles

March 10, 2025

Finding Total Victory on the Road to Championship

I have been playing competitive golf for 55 years. Through the various stages of my life, my…

March 7, 2025

Average Joe Movie: SCOTUS, Praying Football Coach Backstory

When Coach Joe Kennedy knelt to pray at the 50-yard line after a high school football game, he had…

February 28, 2025

The Power of Story: A Muslim Journey to Hope

Storytelling is one of the oldest and most powerful ways to touch the human heart. Parents tell…

February 27, 2025

‘Harriet’ Movie: Courage, Freedom, Faith

Antebellum abolitionist Harriet Tubman had convictions and courage that helped free herself…

Next Steps To Strengthen Your Walk

Inspiration Today Newsletter

Supercharge your faith and ignite your spirit. Find hope in God’s word. Receive your Inspiration Today newsletter now!

Christian Articles

Find articles to strengthen your walk and grow your faith. We have a wide range of topics and authors for you.

Submit A Prayer Request

We are here for you. Simply click on the button below to reach us by form, email or phone. Together we will lift our hearts and voices with you in prayer.