Related Articles

Friendship with Jesus: Finding Joy in the Creator

True joy begins when we know Jesus not only as Savior, but as Creator—and learn to walk with Him in…

Finish Strong with a Kingdom Mindset

For if you keep silent at this time, relief and deliverance will rise for the Jews from another…

The Joy of Being His Workmanship

When life urges us to strive harder and do more, Scripture invites us to rest in a freeing truth:…

Stepping Out in Faith When God Calls You to the Impossible

Stepping out in faith often feels uncomfortable—especially when God calls you toward something that…

Next Steps To Strengthen Your Walk

Inspiration Today Newsletter

Supercharge your faith and ignite your spirit. Find hope in God’s word. Receive your Inspiration Today newsletter now!

Christian Articles

Find articles to strengthen your walk and grow your faith. We have a wide range of topics and authors for you.

Submit A Prayer Request

We are here for you. Simply click on the button below to reach us by form, email or phone. Together we will lift our hearts and voices with you in prayer.

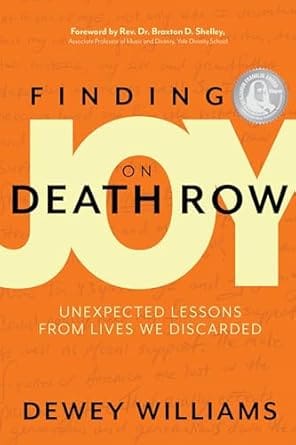

Excerpt taken from Finding Joy on Death Row: Unexpected Lessons from Lives We Discarded by Dewey Williams

Excerpt taken from Finding Joy on Death Row: Unexpected Lessons from Lives We Discarded by Dewey Williams