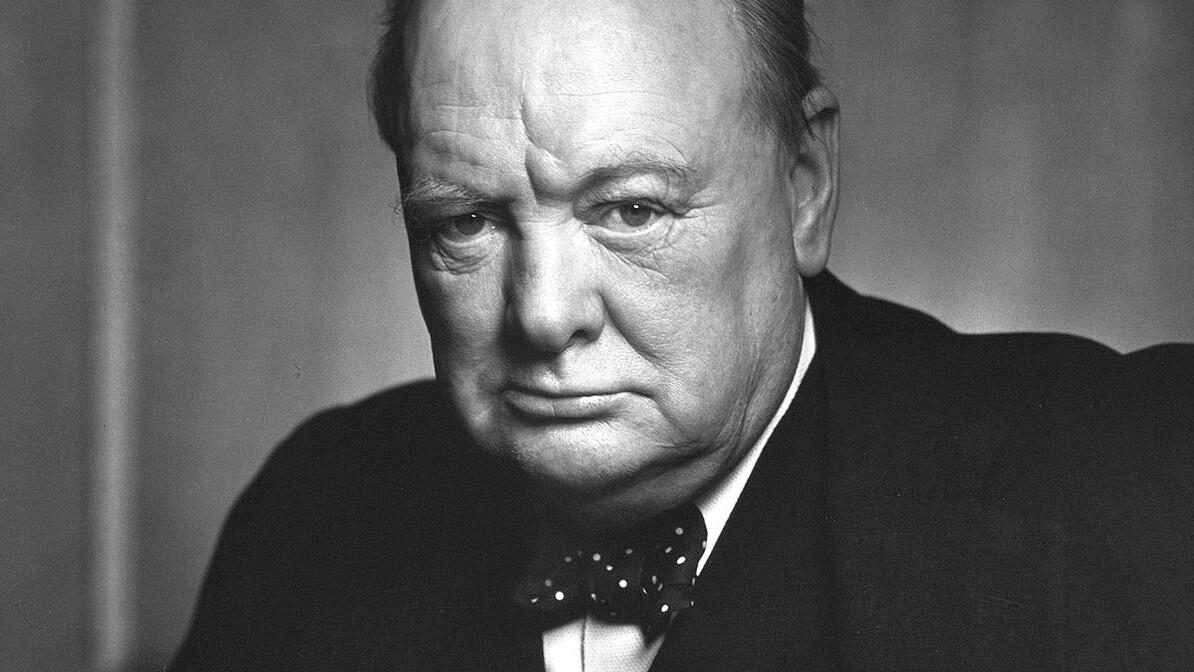

Winston Churchill: When Leadership Mattered

Excerpt from When Leadership Mattered by Baxter Ennis.

Winston Churchill “mobilized the English language and sent it into battle.” Edward Murrow (1954)

Words have power! And, when used effectively by a leader, they can mobilize a nation to victory.

During the dark, early days of World War II when Adolph Hitler’s army was smashing its way through Europe subduing one nation after another, one strong voice emerged to challenge him. That voice was Winston Churchill, the newly appointed prime minister of Great Britain.

On May 10, 1940, Churchill became prime minister. He was “already 65 and, as he put it, ‘ qualified to draw the Old Age Pension,’”[1] yet his bold, courageous words stirred the souls and stiffened the resolve of not only his native Englishmen, but the rest of the world as well.

Many people across Europe believed it was impossible to defeat Hitler. At his trial years later, a leading French collaborator, Pierre Laval, tried to explain his excuse for not fighting Hitler by asking who in their right mind would have believed in anything but a German victory. There was at least one person who didn’t believe it: Winston Churchill.

While other leaders in Britain were ready to give up or talk to Hitler about “terms,” Churchill stood firm! He alone was the backbone of Britain and European resistance to what seemed like an indomitable force.

Appeasement

For the seven years since Hitler had seized power in Germany in 1933, the leaders of Europe had done little to challenge him, but sought to appease him at every turn.

They could have stopped him in March of 1935 when Hitler, in direct violation of the Treaty of Versailles (the peace treaty signed at the end of World War I), ordered the rebuilding of the German military.

In response to the protests of Great Britain and France, Hitler offered vague promises of peace that their governments gratefully accepted. They had no stomach for another war, and his promises gave cover to their cowardice. Meanwhile, Hitler continued building Germany’s military strength at breakneck speed.

They could have stopped him a year later when Hitler again tested the resolve of the two nations by marching German troops into the demilitarized Rhineland—another substantial violation of the Treaty of Versailles.

The contingent of troops was a small, token force of only three battalions, less than 2,000 troops. The German commander was under orders to withdraw immediately if there was any military response from France. There was none!

Even though France had about 350,000 troops, they and their ally, Britain, took no action. They did nothing again but protest. Hitler was buoyed by his unchallenged success.

One of Hitler’s goals was to consolidate all German-speaking people in Europe under German control. When the Austrian president, Wilhelm Miklas, refused at Hitler’s urging to appoint a pro-Nazi chancellor, German foreign minister Hermann Goering took actions to create a “crisis.” He had a member of the Austrian government (who was in reality a German agent) issue a plea for German assistance. Hitler used this fake “crisis” as an excuse to invade.

On March 12, 1938, German troops marched into tiny Austria unopposed, and Hitler announced the Anschluss (union) between Austria and Germany. He brokered a plebiscite a month later for the “official” vote of the Austrians on the matter of Anschluss.

Whether the vote was true or rigged, it is certain Austrians felt the intimidation of the German army inside their borders. When the votes were tallied, 99.7% of the people had voted “yes” for the union. Austria had been annexed and was now part of greater Germany.

The British responded once again with a formal protest which was contemptuously rejected by Adolph Hitler. Again, no action was taken.

The final coup de grace of appeasement was the Munich Agreement. The leaders of Germany, Britain, France, and Italy met for a conference in Munich, Germany, in late September, 1938. At this conference Germany demanded that the Sudeten districts of Czechoslovakia that bordered Germany and contained three million ethnic Germans be given to Germany.

The Czechs refused to give in to Hitler’s demand and asked France to honor their pledge to defend them. However, the weak-kneed leaders of France and Britain, Edouard Daladier and Neville Chamberlain, again sought to appease Hitler and allowed him to seize the Sudeten districts. They returned home with a promise from Hitler that there would be no further territorial claims in Europe. British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain returned to London and proudly proclaimed we have achieved “peace with honor.”

The Munich agreement gave Hitler the Sudetenland at first, but ultimately all of Czechoslovakia.

It is worth noting that had France chosen to fight at this time, they had 100 army divisions and the Czechs had 35 well-equipped divisions. But once again, weak leaders tried appeasing Hitler hoping to avoid another war. Appeasement did not work.

In the early days Britain and France could have easily stopped Hitler and the Nazis in their tracks had they displayed any resolve or courage at all.

Today, as the influence and power of radical Islam is rapidly expanding, there are valuable lessons the West can learn by studying Britain and France’s weak, ineffective responses to Hitler’s aggressive actions from 1935-1939.

One year later, Hitler’s military forces, now formidable, were ready for war! On September 1, 1939, one and one half million German soldiers poured across the border of Poland. The Poles valiantly fought back against this massive “blitzkrieg” lightning attack but were quickly overwhelmed. The Polish Air Force was destroyed in only 48 hours. By the end of two weeks the Polish government had fled to Romania.

The British, finally showing some courage, demanded a German withdrawal. It became obvious rather quickly that wasn’t going to happen, so they, along with France, Australia, and New Zealand, declared war on Germany on September 3. A week later Canada also declared war on Germany and the Battle of the Atlantic began.

By mid-September thousands of British Expeditionary Forces had been sent to the Franco-Belgian border to aid in the defense of France. Then for the next eight months, the “Phoney War” took place on the Western front. The two warring sides took almost no offensive action but mostly sat in entrenchments and stared at each other.

Seven months later on April 9, 1940, the German army went on the offensive again as the Nazis invaded Denmark and Norway.

On May 10, 1940, the Nazis invaded France, Belgium, The Netherlands, and Luxembourg. With this blitzkrieg attack on their neighbors and allies, Britain could no longer look the other way. Real, full-blown war was at their doorsteps!

On that same day, Winston Churchill was appointed Prime Minister of Britain by King George VI. Things were about to change.

On May 13 Churchill spoke to the House of Commons, hoping to gain affirmation for his new administration. In his first speech to the House that day Churchill at once brought clarity, direction and resolve to his nation. In his speech he said,

We have before us an ordeal of the most grievous kind. We have before us many, many long months of struggle and of suffering. You ask, what is our policy? I can say: It is to wage war, by sea, land and air, with all our might and with all the strength that God can give us; to wage war against a monstrous tyranny never surpassed in the dark lamentable catalog of human crime. That is our policy. You ask, what is our aim? I can answer in one word; it is victory, victory at all costs, victory in spite of all terror, victory no matter how long and hard the road may be; for without victory there is no survival. Let that be realized; no survival for the British Empire, no survival for all that the British Empire has stood for, no survival for the urge and impulse of the ages, that mankind will move forwards toward its goal. But I take up my task with buoyancy and hope. I feel sure that our cause will not be suffered to fail among men. At this time I feel entitled to claim the aid of all, and I say, “Come then, let us go forward together with our united strength.”[2]

Finally, Great Britain had a leader! This speech was carried on the radio throughout Britain, Europe, the United States, and all over the world. The effect was stirring and inspiring!

His words were clear, direct, and unambiguous. He intended to wage war on sea, land, and air. And, he intended to have Victory!

However, Churchill was still in a precarious political situation in his own government. He still did not have the backing of the War Cabinet and of major opposition party leaders that he desperately needed.

In the following two weeks, Holland surrendered on May 15. On May 26 the perilous evacuation of some 338,000 British and French troops at Dunkirk began, Belgium surrendered to the Nazis, and France was reeling under the German onslaught, being outmaneuvered and defeated at every turn. It was an extremely discouraging and frightening time.

On May 28 it all came to a head. Churchill met with his War Cabinet in a dingy room in the House of Commons during the afternoon, and a big discussion raged on whether Britain should fight or come to “terms” with Hitler and the Germans. Former Prime Minister Chamberlain and Lord Halifax, who had just recently turned down the opportunity to become Prime Minister, did not support Churchill’s position of wanting to fight the Germans’ advance, and Churchill could not go forward without their support.

The Italian embassy, acting as a mediator for Hitler, had sent a message through Sir Robert Vansittart saying this was Britain’s time to seek mediation. Churchill knew that if Britain accepted an offer of mediation that “the sinews of resistance would relax. A white flag would be invisibly raised over Britain, and the will to fight would be gone.”[3] Churchill said no.

So Churchill left the meeting that afternoon, without the clear support of the War Cabinet, to go meet with the full cabinet. When he addressed the full cabinet, it was the first time many of them had heard him speak as Prime Minister.

This would be one of the most important speeches of his life. He began the speech calmly but ended with a climactic fervor that moved all in the room. He said,

And I am convinced that every one of you would rise up and tear me down from my place if I were for one moment to contemplate parley or surrender. If this long island story of ours is to end at last, let it end only when each one of us lies choking in his own blood upon the ground.[4]

The response was powerful! The room came alive with men shouting and cheering, with some coming around and slapping him on the back.

“Churchill had ruthlessly dramatized and personalized the debate.

When he returned to his War Cabinet meeting at 7 p.m. the debate was over! It was clear to all of them that he had the strong backing of the full cabinet. He had achieved a stunning victory. Britain would fight!”[5]

The news from the battlefield continued to worsen over the next week. On June 4, 1940, Churchill addressed the House of Commons again.

His speech that day was a long, detailed explanation of the situation on the mainland and what had recently transpired. He told about the totally unexpected Belgian surrender of their nearly 500,000 troops that left the Brits scrambling to cover their exposed flank to the sea, a distance of some 30 miles. That was the Brits only possible avenue of retreat.

He told the details of how the Navy and merchant seamen with some 1,100 vessels worked indefatigably under great duress and danger from the sea, the weather, and the enemy to rescue allies from the shores of the English Channel at Dunkirk, France. He told of the heroism and great accomplishments of the British Air Force that inflicted losses of 4 to 1 upon the Germans.

It had been a near miraculous escape for the Brits and the country was euphoric.

As Churchill spoke that day, he attempted to tamp down that euphoria a bit. He noted, “We must be very careful not to assign to this deliverance the attributes of a victory. Wars are not won by evacuations.”[6]

Again Churchill demonstrated amazing leadership. Even though his nation had just barely avoided its largest military debacle since 1781 in the American War of Independence, his speech was indomitable!

We shall go on to the end, we shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our Island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender, and even if . . . this Island or a large part of it were subjugated and starving, then our Empire beyond the seas, armed and guarded by the British Fleet, would carry on the struggle, until, in God’s good time, the New World, with all its power and might, steps forth to the rescue and the liberation of the old.[7]

He was inspiring, resolute, determined! His speech motivated and stiffened the resolve of all.

Two weeks later he would give one of his most memorable speeches of all times. In a radio address on June 18, 1940, he said,

Upon this battle depends the survival of Christian civilization. Upon it depends our own British life, and the long continuity of our intuitions and our Empire. The whole fury and might of the enemy must very soon be turned on us. Hitler knows that he will have to break us on this island or lose the war. If we can stand up to him all Europe may be free and the life of the world may move forward into broad, sunlit uplands.

But if we fail, then the whole world, including the United States, including all we have known and cared for, will sink into the abyss of a new Dark Age made more sinister, and perhaps more protracted, by the lights of perverted science.

Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves that if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say: “This was their finest hour.”[8]

Just four days later, France surrendered to Germany. Britain now stood alone. Churchill tried in vain to encourage continued French resistance to the Germans, but very little resistance materialized, a which was a very big disappointment to him. He continued his ongoing courtship with United States, trying to get them to enter the war. He believed strongly that if he could get the United States into the war the

Allies could win. But this was an extremely hard sell. World War I had cost them more than 116,000 lives, and the Americans wanted no part of another bloody, grueling war in Europe.[9]

The German juggernaut continued to extend its domination. In April 1941 Germany invaded Greece and Yugoslavia. Both countries surrendered within three weeks.

Though at this time Britain stood alone against the Nazis, Churchill remained defiant! In a speech given in late October 1941 he was adamant in his resolve. He said,

Never give in. Never, never, never, never—in nothing great or small, large or petty, never give in except to convictions of honor and good sense.

Never yield to force; never yield to the apparently overwhelming might of the enemy. We stood all alone a year ago, and to many countries it seemed that our account was closed, we were finished. . . . Very different is the mood today.[10]

The Americans would stay out of the war until their hand was finally forced, by the surprise Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor December 7, 1941. The next day, the United States declared war on Japan. Three days later on December 11, 1941, hours after Germany declared war on the United States the United States responded by declaring war on them.

The war raged for nearly four more years and resulted in the deaths of millions of people. It ended in Europe on May 7, 1945, with the unconditional surrender of all German forces to the allies. A few months later the Japanese would surrender after having atomic bombs dropped on two of their major cities.

In those early dark days of World War II, when Hitler’s German army seemed unconquerable, as nation after nation fell to the Nazis, one man, Winston Churchill, stood defiantly against overwhelming odds to challenge the inevitable—When Leadership Mattered.

His resolve, unflagging confidence and determination, inspired his nation to continue the fight until ultimate victory was achieved.

Bonus Notes

- In 1899 while serving as a journalist during the Second Boer War, Churchill was captured and imprisoned. This war was between the British Empire, the South Africa Republic, and the Orange Free State. These two states later incorporated into the Union of South Africa.

- After his daring escape from the Boers, he was celebrated as a hero and became a very successful and well-paid lecturer and author.

- Churchill became Prime Minister on May 10, 1940. In May and June Hitler’s forces were rolling over Europe, and during that time Holland, Belgium, Norway, and France fell, one by one. Great Britain stood alone.

- Belgium unexpectedly surrendered on May 28, taking an army of 500,000 men out of the fight and leaving Britain’s flank and their only route of possible escape, Dunkirk, exposed and vulnerable.

- To understand just how formidable Hitler’s war machine was, we need to consider how long these nations were able to resist before surrendering: Denmark, 4 hours; Holland, 5 days; Yugoslavia, 12 days; Belgium, 18 days; Greece, 21 days; Poland, 27 days; and France, 6 weeks.

- As Prime Minister he wrote his own speeches and radio addresses, typically spending one hour of preparation for every minute he spoke.

- Churchill and Britain stood very much alone for nearly two years, from May 10, 1940, until Dec. 8, 1941, when the United States entered the war as an ally.

- Churchill suffered serious bouts of depression periodically for most of his life. He called his depression his “Black Dog.” At times it affected his sleep, appetite, and ability to function.

It’s hard to understand that after rallying and saving his nation from Hitler’s conquest, he was turned out of office as Prime Minister just two months after Germany’s surrender.

Order your copy of When Leadership Mattered: Inspiring Stories of 12 People Who Changed The World by Baxter Ennis.

[1] Winston S. Churchill, qtd, in Winston Churchill, Never Give In! The Best of Winston Churchill’s Speeches (New York: Hyperion, 2003), p. xxi.

[2] Churchill, Never Give In!, pp. 204-206.

[3] Boris Johnson, The Churchill Factor: How One Man Made History (New York: Riverhead Books, 2014), pp. 11-13.

[4] Churchill, qtd. in Johnson, The Churchill Factor, p. 19.

[5] Johnson, The Churchill Factor, pp.18-19.

[6] Churchill, Never Give In!, p. 214.

[7] Churchill, Never Give In! The Best of Winston Churchill’s Speeches, p. 218. This is from a speech on June 4, 1940.

[8]William Manchester, The Last Lion: Winston Spencer Churchill, Alone, 1932-1940 (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1988), p. 685. This perhaps his most famous speech, delivered on June 18, 1940, to the House of Commons.

[9] Defense Casualty Analysis System, U.S. Dept. of Defense, May 23, 2014.

[10] Churchill, Never Give In!, p. 307. This speech was given on October 29, 1941, at Harrow School.

Trending Now

Sign up today for your Inspiration Today Daily Newsletter

Supercharge your faith and ignite your spirit. Find hope in God’s word. Receive your Inspiration Today newsletter now!

Baxter Ennis

Baxter Ennis has a diverse background in military, academia, politics, publishing, fundraising and community involvement. He served 21 years in the United States Army, retiring as a lieutenant colonel. While serving with the 82d Airborne Division, he deployed on the first aircraft during the First Gulf War. He also participated in a combat parachute jump with the division during the Panama Invasion. He currently serves on the Chesapeake Hospital Authority, has served as president of the Chesapeake Rotary Club, the Virginia Beach Forum, and is President of the Hampton Roads Leadership Prayer Breakfast.

Related Articles

April 15, 2024

5 Small Ways to Save Money Today!

Saving money can sometimes seem like an insurmountable task. Many people feel that they simply need…

April 11, 2024

Dave Says: Be Fair, but Firm

Dave, My husband and I have run our own small business for nearly 10 years. Our largest client,…

April 11, 2024

Starting a New Career at 50

I hear from so many people who are nervous or scared to make a career change in their fifties, even…

April 10, 2024

Turnarounds Through the Power of Prayer

Because of your financial Seeds, God is mightily using the prayer ministers at our Inspiration…

Next Steps To Strengthen Your Walk

Submit A Prayer Request

We are here for you. Simply click on the button below to reach us by form, email or phone. Together we will lift our hearts and voices with you in prayer.

Partner WIth Us

Sow a seed of faith today! Your generous gift will help us impact others for Christ through our global salvation outreach and other faith based initiatives.

Inspiration TV

Watch Christian content from your favorite pastors, christian movies, TV shows and more.